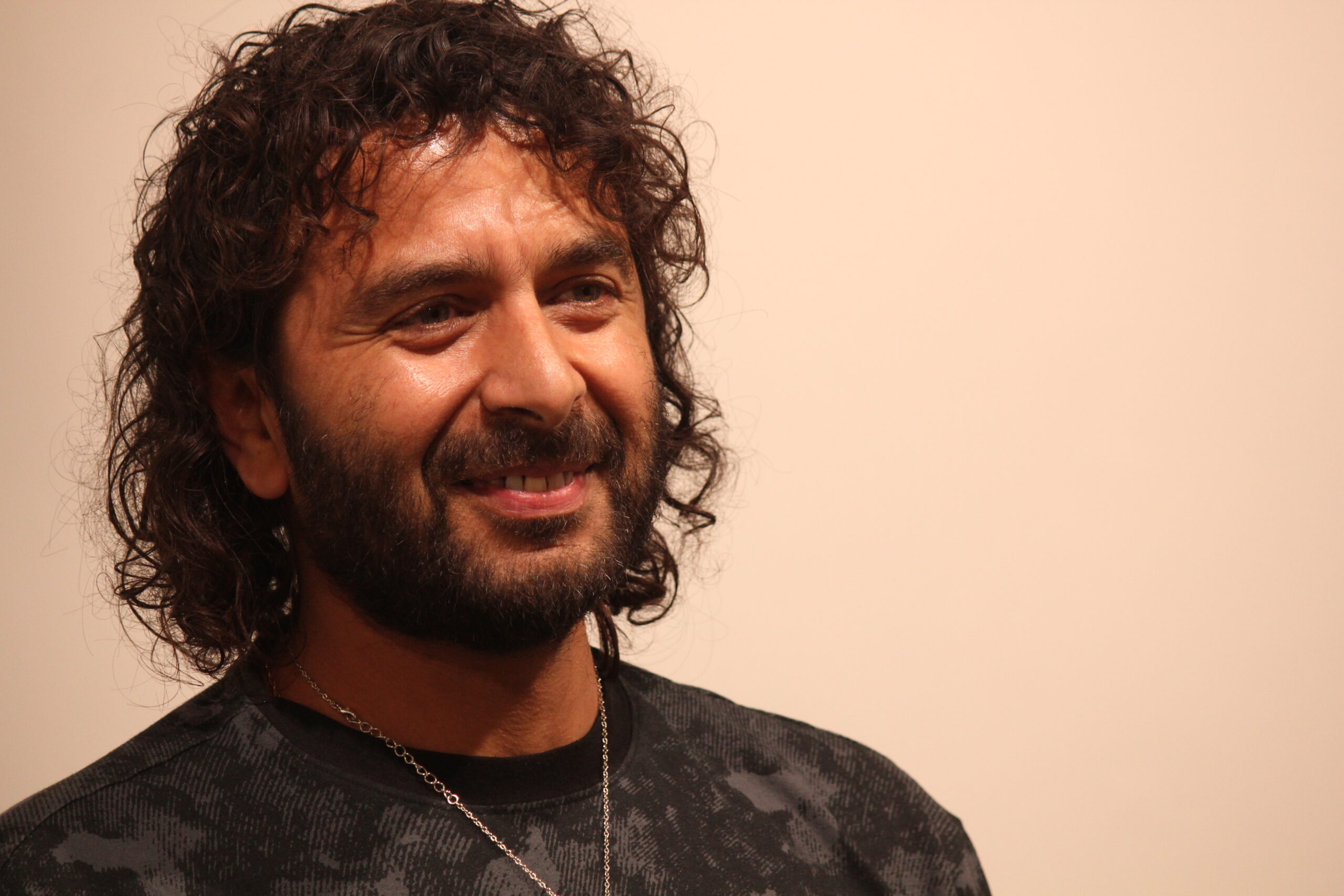

In a world run by AI, advertising and fake news, where everything from films to groceries seem to be owned by some diabolical corporation on a boycott list, the resistance is assembling. While billionaires and corporations harvest reality into monetisable data algorithms, in the backrooms of arts organisations across Bristol, a handful of plucky rebels are plotting to take the fight for technology to them. Bash Malik, a soft-spoken documentary filmmaker now working with AI and VR, is one of those rebels.

Using the tools of mass-market commercial media for grassroots art has long been Bash’s style. In the past, Bash has directed for Channel 4, worked on feature films with the likes of Richard Ayoade and Charles Dance and shot more commercials than he can count. In his melodic voice he tells me about a time he was shooting a Santander commercial with Lewis Hamilton:

“And that was great. Everyone said, Oh, you met Lewis Hamilton! But endorsing commercial banks felt unethical for me. And there were a couple of commercials which were just products not good for the planet, not good for our well-being. So I thought how can I get back to the core reason why I started to become involved in film and making films? And it was all about telling stories of the voices who we don’t see on screen, the unheard voices on the ground, the communities. Creativity shouldn’t be a commodity, it shouldn’t become a corporate entity. And that’s the reason why you choose to stay in the arts.”

Bash has taken what he’s learned in the belly of the media beast and brought it back to the communities he cares about, infusing documentary filmmaking with the lyricism of feature film and the dynamism of music videos: “I wanted to take something that is used in fiction, is using the best production design, artistic quality, the best kit cameras, to create something that now can be used in factual production.” Covering such issues as food inequality, online radicalisation, racism in policing and much more, Bash aims to immerse viewers, going beyond the everyday reportage we’ve become so used to passively consuming: “Our world is all about just clicking, rolling, click, click, click, roll, scroll, watch five minutes and move on. So for me to use this approach, it’s all about keeping the viewer there. Because you can’t just watch ten, fifteen minutes of the story and understand what that human being has been through.”

His recent screening of his documentary I Am Judah, the story of an Easton community elder’s fight for justice after being tasered by police in a case of ‘mistaken identity’, is a perfect example of Bash’s fresh approach to the documentary. Hosted at City of Bristol College, the screening included live poetry, photography, storytelling and group discussion: “The idea is to create an event where we immerse in the narrative, we immerse in the poetry, we see something live, we interact with it. Where we are not just the third person watching it, we become the first person. And having poetry from around the world, having storytellers who talk about injustices in South Africa or stories from the Caribbean or stories from the other parts of the world. I think, again, it’s bringing this sort of global narrative into the space.”

It’s this sense of the most local thing, the testimony of one individual, as being inherently connected to events across the world that drives the politics of Bash’s documentary work: “There are injustices happening all over the world. And for me, it’s imperative to connect what’s happening here to other parts of the world and to engage a global community to maybe learn from what’s happening here and for us to learn from them.” I ask Bash, Why do this as an independent as opposed to working with a major media network? “I want to engage the people on the ground. I want it to be people who are unknown, who are unseen, and to get them seen from the ground up, not top down. And coming back to Diverse Arts Network, that’s what they do. It very much is from the ground up.”

As Bash tells me the story of how he came to work with DAN, I realise its a story I’ve heard before: the story of anyone who’s tried to make art from the margins. “It’s been kind of uncomfortable at times to get into that space and to build the confidence or to flesh out ideas that have been kept locked away in this sort of lock in the stomach, thinking, ‘I don’t think I’m good enough’, or ‘I don’t think these ideas are gonna go anywhere.’ And suddenly, when you have support, it comes out.” Through DAN, Bash has found not just an agency, but a collective that is fundamentally against exclusion, where artists can come together to foster independence. “Diverse Artist Network has people from all walks of life. Diversity is everywhere and we need to value that. It’s about creating something that involves everyone, not just the majority.” I ask Bash about his recent poetry reading at the DAN showcase at Malcolm X community centre. As he speaks, his eyes flash and a self-conscious smile spreads across his face.

“There’s an open mic and no one was signing up for the poetry. So Vandna said, Right, put Bash down. It’s like, what? No, I’m not on the stage. I don’t do stage. It was like a big kind of deal for me and it sort of, you know, just gave me this feeling that this is great this is really good to be pushed. But yeah, Vandna pushed me into it and Deasy, who are the founders of Diverse Artists Network. And since then, they’ve been pushing me into other spaces regarding the whole idea around tech. Even though those ideas were in my head for months, I didn’t have anything sort of there, external, out of me. It was just in my mind, in my brain.”

But these ideas aren’t just in Bash’s head anymore. For most people, the association between new technology and corporate control just seems obvious. But for Bash, this easy association is part of the problem: “Tech has been historically something that we see in the hands of the corporate giants or governments. And I’ve come to the realization that, if we allow this to continue, we are gonna be the ones who are left behind, working out what is it that’s actually happened to us.” Bash chooses to see the other side: “Communities can come together and connect through tech. And I want to try and create something that offers a way that we can use tech so that, one, we can grow as artists, but also, two, we can engage lots of different communities to use tech for good.” This need for inter-community dialogue is the inspiration for Bash’s upcoming VR experience, Come Walk In My Shoes, in which players can experience in first person what its like to walk down the streets as someone else:

“Those shoes are the shoes of many. It can be the shoes of a refugee, the shoes of someone who’s transgender, someone who is a black doctor or a patient. The slight gaze by someone who might walk past you wearing a burqa, it means nothing to the person who’s looking. But for the person receiving it, that could just be such a heartbreaking experience to go through daily life like that.”

In Bash’s hands, VR isn’t just another toy for the wealthy, but a tool for solidarity, helping us to imagine perspectives that are not our own. Just like his documentaries, through VR we are not just the third person watching, we become the first person.

But that’s only one of the things Bash is working on. He’s got two AI projects in the works, one of which is top secret. The other is his ‘stop and search chatbot’: “You can speak into it and say I’ve just been stopped by the police, what can I do? And it will give you options of what you can do and potential legal assistance you can access there and then.” While governments and corporations use AI to enhance policing, Bash’s team are using the same tech to fight back.

Talking to Bash about VR and AI, I can’t help but feel embarrassed by my own personal ignorance towards these things. That is until Bash tells me that, before working with DAN, he felt the same way: “It’s really overwhelming because I just didn’t really ever dream of something like this happening because I just have no experience with tech.” But, as far as Bash is concerned, when people come together anything is possible: “I want these partnerships. I want organizations where we work together, where we come together. If you believe in me, right, I believe in you. Let’s make it happen. Let’s create something that can be really powerful.”

Did you enjoy this article? Share it via:

Written by Charli (they/them). Charli is a literary critic, researcher and writer originally from London. They study queer experimental literature and art from 20th century to present. In addition to completing their Masters, they have presented research at academic conferences and been published in University of Bristol’s Student Research Journal.

Charli is interested in bridging the gap between academic and practical approaches to understanding creativity and social justice. They began working with RISE in 2024 at We Out Here festival and have since interviewed a number of creatives in collaboration with initiatives such as Diverse Artists Network and Compass.

This interview is a collaborative production by Diverse Artists Network and RISE Collective as part of the Artists Spotlight series. This series aims to showcase the diverse talents and creative journeys of artists across Bristol and the South West. This initiative aligns with both organisations’ commitment to promote diversity, representation, and inclusivity within the arts.

Leave a Reply